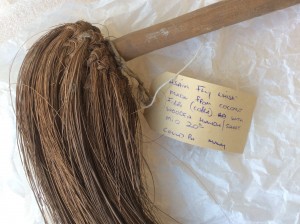

Image courtesy of Bexhill Museum.

Arriving in Borneo and focus shifts from Annie’s “A Voyage in the Sunbeam” (1878) to her posthumously published “Last Voyage” (1889). Borneo, and the caves therein, triggered the deterioration of her health after catching a fever. Annie had suffered with her health for a long time, particularly with malaria, although she also commented on her arm troubling her at times, thought to be due to a riding accident (Julian Porter, curator, conversations at Bexhill Museum). The caves in Borneo and the story of their role in Annie’s deteriorating health are the reason I included Sabah (Malaysian Borneo) in my itinerary. Transfixed by the existence of the caves and discovery that the birds’ nests she went in search of, now held at Bexhill Museum, committed me to this journey and planted the seeds for this residency (and ‘In Conversation with Annie‘).

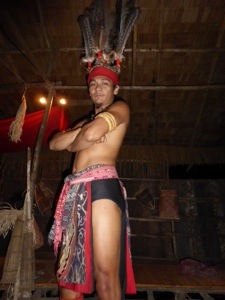

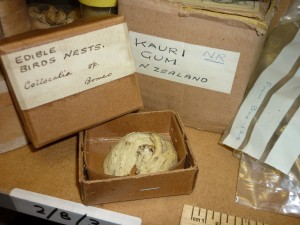

Birds’ nest, courtesy of Bexhill Museum.

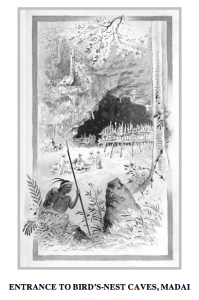

Annie’s interest with Gormatong and Madai caves was principally the habitation of the swiftlets within and their nest building. Prized for the soup, a particular delicacy in China, birds’ nests would be collected from within the caves and boiled down to make a glutenous liquid for serving. My interest was particularly piqued through Annie’s accounts detailed in “The Last Voyage” and the accompanying illustrations. It is described as quite an adventure to find said caves and the sense of far away lands are especially evident here.

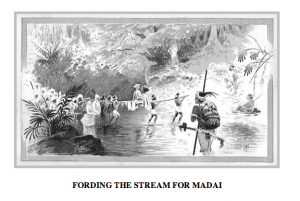

Entrance to Madai Caves, image courtesy of Bexhill Museum.

Black bird’s nests caves, Madai caves, Borneo “looking awkward” (Lady Brassey photograph collection, with kind permission from Hastings Library)

Gormatong Caves (Louise Kenward, 2014)

Swamps and rainforest eventually precluded Annie from reaching Gormatong. Men were sent to find the caves and she accepted defeat only after three day treks proved the challenge of reaching them. She had to be satisfied with Madai. In contrast I had gone in hope of finding Madai caves and had to settle for finding Gormatong. They were a good deal more accessible than they were in 1887, although much of Northern Borneo is still a little challenging to navigate without your own transport (and all the correct permits). They did look similar to Annie’s photographs of Darvel Valley and Madai caves and I trust smelled the same (I was fortunate to be harbouring a cold by then). The floor covered in guano, the walls in cockroaches. There were men living inside guarding the valuable bounty and rickety wooden ladders lashed together as Annie describes. The main difference was not at the caves themselves but when I came to leave Borneo. Arriving at the airport for my flight to Australia, I spotted a shop window filled with clear perspex boxes, each filled with small white birds’ nests.