While I travelled in one direction, more or less, the journeys of Annie’s that I tracked were multiple. This meant that mid way through my journey, and just as I arrived in Australia, Annie died. It was not unexpected, I knew the date, time and place, but it was still met with sadness and some pause for reflection. It didn’t mean the end of Annie as travel companion, but from here on in I was travelling backwards through time, as far as Annie was concerned at least.

The last place the Sunbeam docked before Annie’s demise, was Darwin. This was the point of arrival for me in Australia, making my reaching this new world full of mixed feelings. Losing Annie here was a blow, she had, by that stage almost completed an entire loop around the country, and I had grown quite used to my virtual companion. I’d become quite attached, the process of travelling, of writing, had led me to find a strengthening connection.

Early morning, Darwin waterfront (Louise Kenward, 2014)

Arriving at dawn to a whole new world, in every sense, I experienced the ‘reverse culture shock’ often cited by travellers returning home after long journeys, adding to my sense of disorientation. I hadn’t expected to experience it mid way through, but after travelling through so many poorer parts of the world, adapting and establishing routines of one kind or another, to arrive in (an apparently) squeaky clean, shiny and empty Darwin took me by surprise. I had arrived after four months of crowded streets, bustling markets, squat toilets, mopeds piled with everything and anything (including the kitchen sink, entire families and livestock), it was noisy, colourful, chaotic. I loved it. Darwin was silent. Its wide pothole free tarmac streets empty. When a car did appear on the street it spotted me and stopped, allowed me to cross the road. I was dumbfounded. The best travel advice I have ever read is about crossing roads in Vietnam “just walk, keep walking, keep a steady pace and everything will drive around you” and that’s how it happens. I was well practised by now at crossing apparently impenetrable roads. For something to stop for me to cross, especially when there was nothing else on the roads, captured a whole sense of being somewhere else, somewhere new, somewhere surreal and unexpected. It was unsettling. I walked to the waterfront. The sea is a constant. It soothes. The only people I saw at 6am were joggers. No taxi drivers, tuk tuks, men chasing me down the road wanting to mend my shoes. No market stalls, no one tried to sell me anything or get my attention. Just a couple of joggers. One of whom said ‘g’day mate’ and truly sent my head in a spin. Living up to stereotypes I had walked into the set of neighbours perhaps, a TV version of Australia. Finding public toilets was the next shock. They were open, they were clean, there was running water, it was hot, there was soap and somewhere to dry my hands. There was even toilet paper in the cubicles. I missed Asia terribly. I didn’t know what to do in all this brilliant white sparkling new place. It seemed unblemished and sanitised. I felt very much on my own. Added to that the stark reality (of sorts) that this was the last place Annie visited it made for a surreal experience where I questioned the ground under my feet.

Revisiting then, in the context of Bexhill Museum and the collection held, I am reminded of many of the things that I am continuing to grapple with and understand better. The Aboriginal culture was not evidenced in the Irish bars or the smart cafes of Darwins’ wide streets. Travelling to one of the National Parks, Lichfield, was my first taste of the incredible country and rich history of Australia. Arriving in the wet season, Kakadu and its examples of Aboriginal art were temporarily cut off. Roads flooded. Impressive termite mounds the area is famous for gave me some impression of this being a different land like no other. I chose not to visit crocodile ‘side shows’ designed for tourists, entertained by the proximity of wild and hungry animals. How tantalising it is to be in the presence of creatures with the power to kill you. And as you enter Australia you are told ‘everything can kill you’.

Oceania cabinet, Bexhill Museum (Louise Kenward 2015)

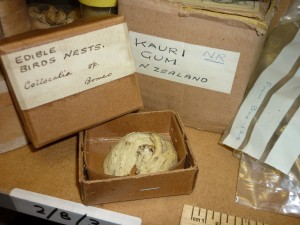

Alas, I digress, I will return. For now I will illustrate my day ‘In Conversation with Annie’ and some of the objects from Northern Australia held at Bexhill Museum. Spears with heads made of beer bottle glass, axe heads of granite and shell pendants decorated in geometric designs. Many artefacts refer to the early settlers arriving in Australia. Planning to run some workshops in the near future I decide to experiment with my own drawing practise and return to using charcoal, trying out some of the things I think might be interesting for others to try. Of some of the wonderful things on display it is a little disappointing the North Australian objects are not especially appealing to draw. An axe head of granite and spears…a challenge. Rolling out paper on the floor in front of the cases, kneeling with charcoal and putty rubber, it is nonetheless an interesting exercise. I consider how vast Australia is, how much variation there is likely to be in objects and designs and I enjoy a return to working with charcoal, the challenge of yet another new texture to attempt.

Working at Bexhill Museum, charcoal & pastels on lining paper (Louise Kenward, 2015)

The process is enjoyable. Working in another part of the museum, feeling more connected to the gallery spaces (literally and metaphorically as I sit on the floor), it feels as though there is at last some loosening up. Movement is key. Different positions of sitting, drawing, different materials. Working with things behind glass pose their own difficulties but with recent experience I imagine handling the spear heads, engaging sense of touch even on a virtual level. The sharpness of the tips, smoothness of the spearhead and consider the making of them, the person who had formed this one I select as my favourite in Northern Australia over a hundred years ago.